Facilitation is such a great opportunity to nurture honest communication among different personalities; to find both common and uncommon ground.

As I was talking with one client about goals for an upcoming meeting of board members from different organizations, she happened to let drop that one participant was known to take over meetings. Apparently, at a recent City Council meeting, he had talked most of the hour and a half – in the face of many distressed faces looking back at him.

Yikes! It was tempting to fear the worst for my upcoming facilitation gig. This fellow had the potential to derail the entire project. I had some strategies but worried that maybe I was missing something.To get some fun tips and great ideas, I thought I’d do a little crowdsourcing. I turned to the National Network of Consultants to Grantmakers (NNCG) email list as well as another consultant’s email list and a facebook group of consultants. I asked the wise people in each of these groups for great strategies to limit dominant personalities’ air time. I wanted to hear what they had to say – while encouraging quieter folks to also pitch in their thoughts and ideas.

Responses were prolific! Apparently, I’d hit on something that people had experienced and were eager to say something about.

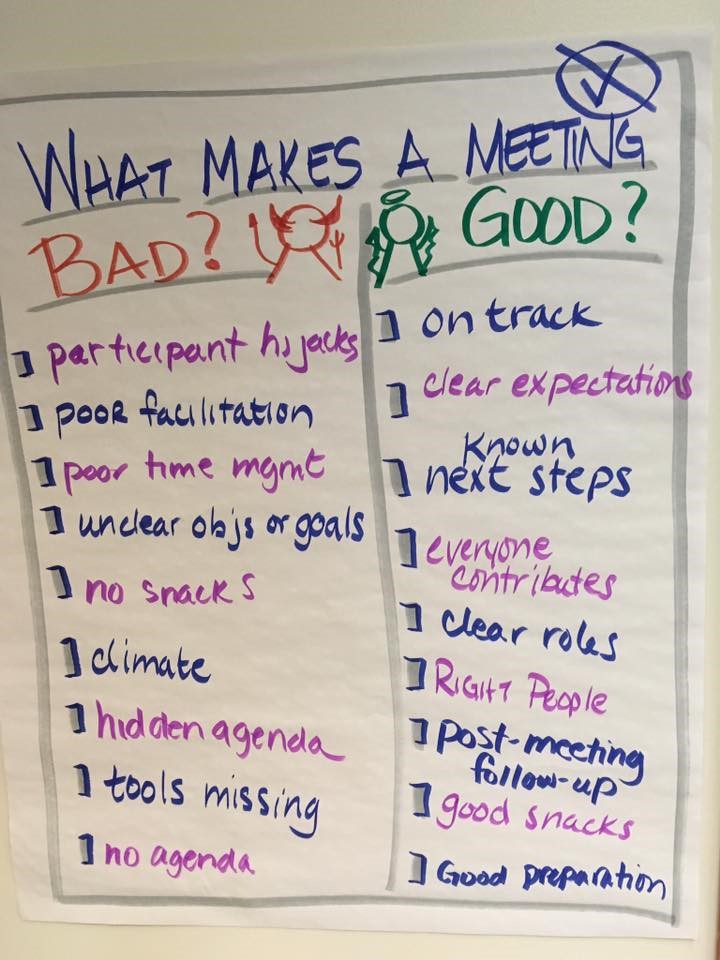

The most common response by threefold was to establish ground rules at the outset of the meeting. (And I must give a shout-out here to my wonderful friend Vega who takes a different position on the topic – see her blog post opposed to ground rules here.)

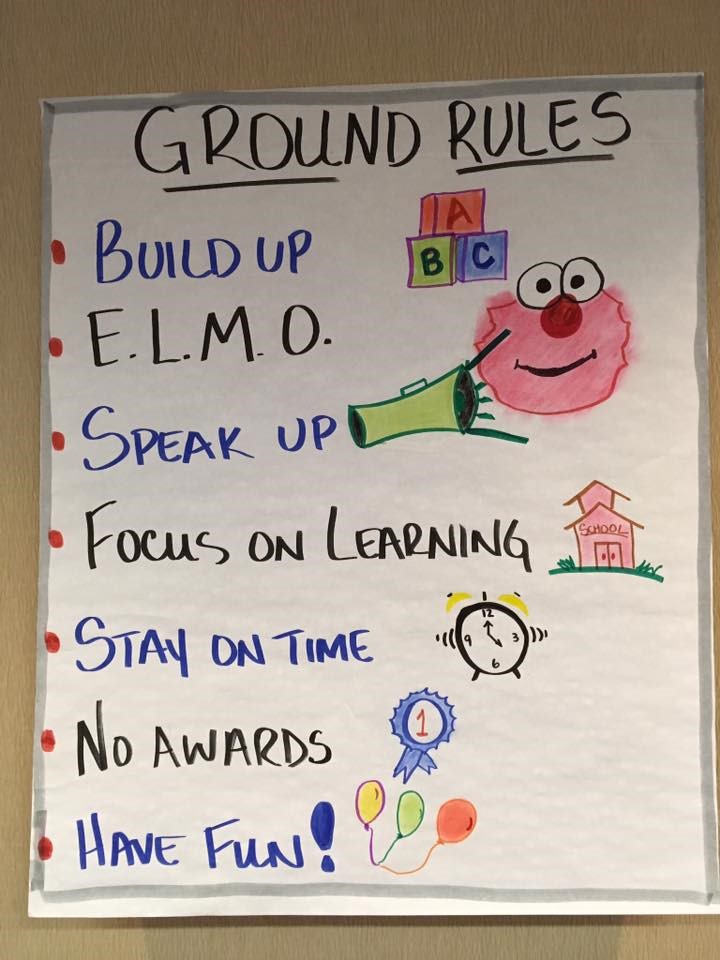

Ground rules go by other names, e.g., “shared agreements” or “community agreements.” They can be set forth by the facilitator; proposed for approval; proposed for discussion; or crafted from scratch by the group – depending on all the obvious factors (how much time there is, the facilitator’s style, the type of group, etc.). One strategy is to have just one rule, dubbed the “North Star,” along the lines of asking participants to ask themselves, “Is everyone benefitting from what I am saying?” Additional good ground rules are in the images in this post, provided by generous facebookers.

Other suggested ground rules were:

- WAIT (ask oneself, “Why Am I Talking?”)

- “3 and me” (3 others have to talk before the first person can speak again)

- “Step up/step back” and its variants, “step up/step up” or “lean in/lean back” or “make space/take space” or “raise up/raise up” – alternatives to the original, which can be perceived as ableist in suggesting that all participants can take literal steps)

There was a second group of ideas that each got several mentions (in order of frequency):

- Cut them off (in various creative ways, from bluntly to humorously). Example: Clap loudly once and say, “1, 2, 3, eyes on me.”

- A range of strategies to distract and divert, including: have people talk in small groups and report back; use a 3-part strategy of Think/Pair/Share; paired discussions.

- Use “Stack,” in which names are jotted on post-its and put on one’s hand or on the wall in the sequence in which speakers may contribute).

- Use a Talking Stick (or related: any sacred object, a fake microphone, a “smarty toad” or other stuffed animal).

- Explicitly ask others to chime in by name.

- Name the problem in the moment, which can range from, “Thank you, but you are speaking more than anyone else and we want to hear from others, too,” to a gentler strategy that might sound like “I like what Mr. Smith is saying; he has some great points” then turning to the rest of the group and asking, “who else has ideas to share?”

- Create a parking lot/garden plot list on a flip chart; when someone speaks too long, put their topic on the list, “Great point; if we have time, we’ll come back to it later.”

One tip that warrants special mention is a book recommendation: “The Power of Protocols,” which got two mentions. I purchased it, and sure enough, it’s packed with one idea after another. It’s focused on educational applications, and many of the protocols are easily transferred to facilitation generally. If you’re seeking a deal or want to buy outside of the box, you might find it at Powell’s Books or Alibris. Otherwise, it is, of course, also on Amazon.

There were plenty of other ideas that got one or two mentions. Some of these are just plain terrific; others would only work well in certain situations; good to keep in our back pockets. In no particular order below. Enjoy!

- Create lots of structure, such as having—and sticking to—an agenda.

- Stand right beside or behind the dominating person to throw them off their guard.

- Use humor.

- Do straw polls before opening a topic for discussion.

- Have people raise their hands when they want to speak and, when an over-talker raises his or her hand first, count to 10 (silently) before calling on them to see if someone else has something to say.

- When this happens, if the facilitator is a woman, how much of this is mansplaining?

- Use a timer or assign a timekeeper separate from the facilitator to keep the conversation on track.

- Scribe what is said, giving quieter people as much “ink space” as over-talkers, to create a more level dynamic.

- Identify possible distracting behavior or topics in advance and develop solutions to implement.

- Distribute surveys after the meeting (my comment: this is likely more effective in creating a productive meeting if it’s announced at the beginning—effectively putting the dominant personalities on notice that they are open to criticism from their peers).

- Have one-on-one conversations with participants in advance so they can blow off steam and be more open to hearing other perspectives.

- If a meeting gets very contentious and many people are talking over one another, enforce 5 seconds of silence before anyone speaks again.

- Name the problem in advance: “We’ve had meetings where one or two people dominated the conversation during the meeting. This results in a less effective meeting, and other people don’t get to share their ideas. This situation is having an impact on our group’s ability to get our work done.”

So…with this outpouring of input, what did I do? What happened when I facilitated with my client?

First, I opted into lots of structure, starting by distributing a very clear agenda that had been approved in advance by my client (and I said so). Second, I emphasized at the beginning that one of the goals of the meeting was to hear from everyone. Third, I built in time for participants to talk in pairs or triads and then report back on what someone else had said.

And the gentleman with the bad reputation? He spoke from time to time, made valuable contributions, and didn’t talk over others. Not once!